By William Raven

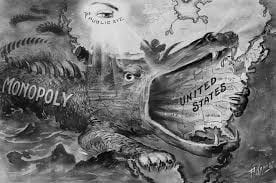

“Google was the original gateway to the web. I’m here today to speak about how Google betrayed the web” stated Yelp policy head Luther Lowe at a Senate hearing on digital platforms focusing on anticompetitive practices. “Google physically demoted non-Google results even if they contained information with higher quality scores” further claimed Lowe as he took the witness stand at the hearing, imploring the Senators present to accept his contention of unfair competition. The recent hearing was conducted in order to gain additional information to bolster several tech and antitrust bills that await passage in the Senate. Perhaps the most ambitious of these bills is the Monopolization Deterrence Act of 2019, authorizing the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission to enforce civil monetary penalties in order to deter violations of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. Former Presidential Candidate, and Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar, sponsors the bill which she states would allow “serious financial consequences” to impede the nation’s “major monopoly problem.”

The proposed Monopolization Deterrence Act would impose penalties as high as 15% of a company’s total revenue in the United States of the previous calendar year, or 30% of the total revenue related to the unlawful conduct, whichever amount is larger. Despite the Sherman Act’s preeminent enforcement provisions allowing for money penalties of up to 100 million or more depending on the amount of money lost by victims of the crime, the sponsoring senators believe more aggressive monetary penalties are necessary as more and more companies become too big to feel the sting of infractions under current regulation.

Perhaps the impetus spurning the need for more extensive anti-monopolistic regulation is the exponential growth of the mega-corporation. At the time of the Sherman Act’s passage in 1890, large modern corporations were a relatively new phenomena, the operation of which were not understood clearly by the public at large or the law-making bodies of Congress. Today, as behemoth companies become the norm in providing service and products to customers, the breadth of the Sherman Act becomes more important. The valuation of the top tech companies elucidates this fact with Apple, the largest of the bunch, being valued at 951 billion dollars, Amazon valued at 828 billion, and Google’s parent company Alphabet valued at 781 billion dollars. In fact, “Big Tech” is often used to refer to Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google and Microsoft, highlighting their massive market power and thus influence upon the American technological market.

“Big Tech” has become a pejorative term for a number of reasons including the ability to control prices which inflate the market, and the destruction of innovation and disenfranchisement of small business, eliminating competition. In fact, Elizabeth Warren and her supporters called for an even greater measure to stem the influence of the big tech companies—their breakup. Calling for the division of Amazon, Google, and Facebook, Elizabeth Warren states that these companies have too much power, “too much power over our economy, our society, and our democracy”, which harms smaller businesses and prevents innovation. To highlight, greater than half of all e-commerce originates with Amazon; whereas, Google or Facebook owned websites garner 70% of all internet traffic.

A direct result of the non-enforcement of antitrust laws is the ability of these tech giants to purchase or drive smaller competitors out of business. This reality leads to the dearth of venture capitalist investment in funding new startup companies as the prospect of them competing with the giants seems outlandish. The lack of competition means that organizations like Facebook are able to define what is normal in the market—which for them includes lax privacy precautions, and an immense political power, enabling the company to act “more like a government than a traditional company” as professed by none other than Mark Zuckerberg.

Although the Monopolization Deterrence Act of 2019 may serve as an additional hammer of justice from which large tech companies may feel its impact, ultimately the provisions of the Act are more of the same. The solution to the anti-competitive nature of these tech giants cannot be found through the levying of a fine. As previously expounded upon, these companies are so large as to function as quasi-government bodies, able to influence legislation and spur municipalities to fawn over the jobs and business they bring to an area. Further, the additional monetary enforcement provisions are indeed greater than they now stand, but not by a large margin. The sheer power of these companies makes the imposition of any fine merely an annoyance, of which the cost is undoubtedly passed along to the ultimate consumer.

The most prudent answer to quelling the overbearing influence of these large tech companies may be found in another piece of proposed legislation, the Consolidation Prevention and Competition Promotion Act of 2017. The Bill, again sponsored by Amy Klobuchar, provides for an outright ban on acquisitions for companies with a market cap above 100 billion. This would lessen the importance of attempting to forever increase the fine amount that may be levied on a company, instead focusing on the entity’s ability to usurp any competitor. Indeed, Matthew Stoller of Open Markets’ states that the best remedy to protect against Google’s dominance is “to block Google from being able to buy any companies.” Google has added more than 200 startups to its portfolio since its founding including YouTube, Android and Nest. The Consolidation Prevention and Competition Promotion Act would ban these types of acquisitions by companies such as Google, allowing these smaller businesses to grow without the fear of being forced to be swallowed by such a gargantuan as Google. As innovation stems from the emergence of new and competitive ideals, the blockage of Big Tech companies from acquiring budding startups inevitably will provide greater diversity for the consumer, affording choice in the largely homogenous world of tech solutions and products.

Student Bio: William Raven is currently a second year law student at Suffolk University Law School. He is a staffer on the Journal of High Technology Law. Prior to law school, William received a Bachelor of Arts Degree in English from the College of the Holy Cross.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog are the views of the author alone and do not represent the views of JHTL or Suffolk University Law School.