POSTED BY Alexandra Lowe

In 1994, Police Chief William Bratton introduced computer-driven performance management to policing. This data-focused management model, originally known as CompStat, is credited with introducing the concept of “predictive policing” to law enforcement and crime fighting. CompStat and other similar programs synthesize close to real-time crime data in order to identify criminal patterns and problems. A 2013 study, found that the technology could be used to predict the place and time of crimes and predict and identify the profiles of likely offenders and victims. The practice of applying predictive policing technology to crime fighting has significantly reduced crime when and where utilized. By eliminating certain variables in criminal acts that may have previously been considered “random,” police are better able to focus their efforts and resources.

One technology tool being utilized is the automated license plate reader (ALPRs). Although such tools have been around since the 1990s, the technology has become extremely popular in recent years. ALPRs are cameras mounted to patrol cars and fixed sites, such as bridges or intersections, that capture and store data of the license plates of vehicles passing by. ALPRs provide geographical, date, and time information on license plates and the records can be stored for up to two years. Police departments have used such data to track a vehicle used in a crime, identify vehicles near a crime scene, aid in arrests for grand larceny, and recover stolen vehicles. Understandably, such location and time-based data could be invaluable in the enforcement of the law in a variety of crimes and proceedings. However, privacy is a huge concern.

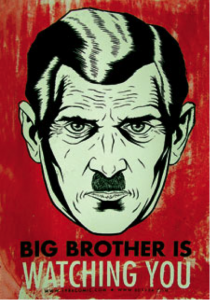

ALPRs record license plates automatically and indiscriminately. This enables police to collect extensive location data on an individual both without the individual’s knowledge and without any level of suspicion on his person. Civil liberty groups and advocates fear ALPRs could degrade personal privacy while others are less concerned. Some argue police will use ALPR in a targeted fashion, only focusing on plates with suspicious activity or the subject of an investigation. Others are concerned that the government could track their every movement, revealing their comings and goings, habits and associations. Others are concerned with how long such data can be archived – some arguing twelve hours is legitimate to aid in crime fighting while others believe such data should be available indefinitely.

It is clear that ALPRs could have an immense impact on law enforcement and the administration of justice. Currently, however, the negative ramifications of ALPR technology are less known but still disquieting. Is there a way to limit an inherently and necessarily invasive tool through legislation? What, if any, protections could be provided to a “law abiding” citizen? Essentially with the use of ALPRs all persons are being investigated at all times.

BIO: Alexandra Lowe is a Staff Writer on the Journal of High Technology Law. She is in her third year at Suffolk University Law School and currently a law clerk with Margolis & Bloom, LLP.

You must be logged in to post a comment.