By Harrison Lebov

In recent days, following the much anticipated first presidential debate of this political season, the topic of “stop and frisk” returned to the front pages of newspapers and tabloids. Donald Trump, Republican presidential nominee, caused quite a stir when he suggested bringing back stop and frisk tactics in an effort to reduce the number of illegal firearms on the streets. Much to readers’ dismay, Mr. Trump wasn’t completely wrong, but he also wasn’t necessarily right either. For starters, the procedure of stop and frisk was legitimized in the landmark case of Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968). In Terry, the United States Supreme Court affirmed the Ohio Supreme Court’s ruling that the Court rightfully denied the Defendant-Petitioner’s Motion for Suppression on the basis of a Fourth Amendment violation. Mr. Terry, Petitioner, alleges that a police stop followed by a pat-frisk by a police officer violated his Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable searches and seizures. The officer stopped Mr. Terry after watching him stake out a jewelry store, pacing past the storefront on the street multiple times, and conversing with a couple associates. The officer stopped Mr. Terry and a subsequent pat-frisk revealed that Mr. Terry was in fact carrying an illegal firearm, which was eventually the evidence that Mr. Terry attempted to suppress at his trial, but that motion was denied. The Supreme Judicial Court affirmed the lower courts’ decisions to deny the Petitioner’s motion on the basis of a few important, underlying, “specific and articulable facts.”

The decision of the Court was based upon a finding that the police officer had reasonable suspicion – not to be confused with the higher standard of probable cause – that a person has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime. The purpose of the rule enumerated here was prevention of violent crime where the suspect is reasonably believed to be armed and dangerous. If a finder of fact determines that the facts of a particular case do indeed reflect that rule, then the interests of justice and public policy will have been served by a police officer’s decision to stop and frisk. Unfortunately, somewhere along the way, the line became blurred and the stop and frisk was not applied as stringently as the courts likely intended, or may have been used for more insidious purposes.

Terry remained good law for a number of years, and to this day is still good law if applied correctly. The baseline of the “Terry stop,” as this procedure has come to be known, rests with the assumption that the arresting officer has a reasonable belief that a crime is in progress and that the suspect is armed and dangerous. However, problems arise when the cause of the stop is unjustified, and the resulting pat-frisk is thus unwarranted and unreasonable under the Fourth Amendment. In Floyd v. City of New York, 959 F. Supp. 2d 540 (S.D.N.Y. 2013), a citywide stop and frisk police mandate was found to be unconstitutional, more specifically, violative of the right against unreasonable search and seizure under the Fourth Amendment, because of a systematic, discriminatory practice of targeting racial minority groups without the requisite reasonable suspicion necessary for a stop in the first place.

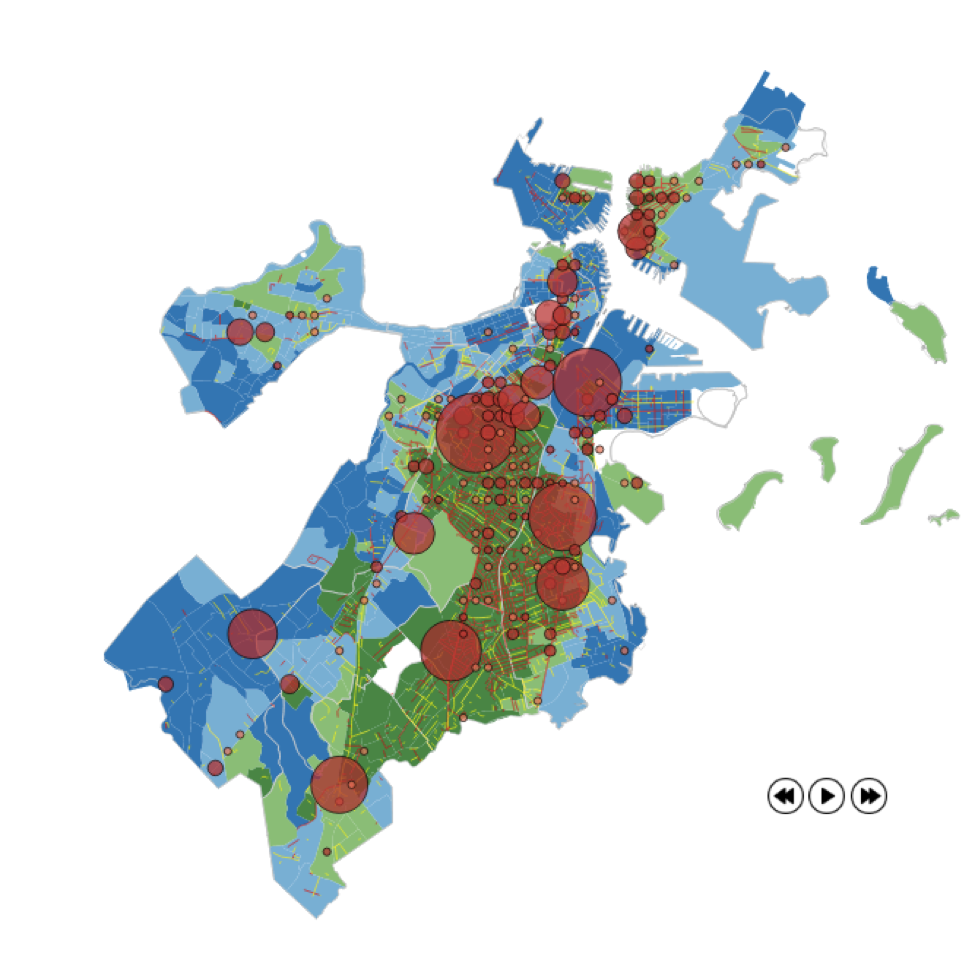

It is at this point in the conversation where readers are encouraged to turn their attention back to the top of this post and take a second look at the image above. It is one thing to hear the bottom line, but it is another thing to see it, and that is precisely where data analytics come into play. Data analytics, by definition, is the science of studying raw data with the intent of taking that information and presenting it in a way in which conclusions can be drawn therefrom. Now, rather than having to crunch numbers and analyze for yourself, data analytics can be used to form visual representations of the data set. Think of this part of the post as a key or legend for the posted image, which is a color-coded map of the city of Boston circa 2010. The blue plots of land represent areas populated primarily by white people, and the green plots of land represent areas populated primarily by black and Hispanic people, or people of color. The darker the area, the more highly populated the area is with the corresponding races. The streets that are lined in red represent the streets that stop and frisk searches were conducted, and the red dots represent drug arrests and/or drug investigations.

In 2010, when the data from this picture was gathered, Boston had 617,594 residents, about 47% of whom were white, and about 53% of whom were people of color. Like many other major United States cities, Boston is somewhat racially segregated, but it does not take a data scientist to tell you from the depiction above that there is a legitimate discrepancy between the population as a whole and the population subjected to stop and frisk searches. One critical fact that this data does not examine is whether these Terry stops were constitutional or unconstitutional – whether these pat-frisks were supported by reasonable suspicion for the stop or not. Because the data at hand does not provide for such analysis, it may be helpful to examine the data underlying the case in Floyd from New York.

Between 2004 and 2011, 83% of Terry stops were made on black or Hispanic people, and only 10% were made on white people. These results seem to be consistent with the data gathered in Boston in 2010; a vast majority of the stops were made on people of color. Because this issue turns on reasonable suspicion for the stop, a finding of constitutionality depends on the validity of the stops in the first place. Of all the Terry stops made between 2004 and 2011, only a mere 1.5% of stops produced a weapon, and 88% of stops produced neither an arrest nor a summons. Again, it does not take a data scientist to conclude that these stop and frisks, in general, were not supported by reasonable suspicion of a crime in progress or the presence of a firearm.

It logically follows that these stops, in general, were racially motivated or the result of racial profiling, although there was likely implicit bias in play as well. In the alternative, and less pessimistically, these lopsided results could also be attributed to high crime areas being mostly populated by people of color. So it logically follows that if police more often stop and frisk people in high crime areas, more people of color will unavoidably fall victim to those stops, irrespective of race. There is no doubt that the data seems to indicate a systematic flaw in the way stop and frisk tactics have been implemented, whether that flaw is attributed to racism on its face, or mere circumstance or happenstance. The cause of this statistical discrepancy is not necessarily racist policing, not to foreclose the possibility that it may be in some situations, but correlation does not always equal causation; post hoc ergo propter hoc, which is Latin for “after this, therefore resulting from this,” is a logical fallacy that just because one event follows another event, the first event caused the second event. Regardless of the subjective intent of the investigating officer, whether motivated by race or not, the statistics clearly indicate that inefficient policing is a legitimate issue and ineffective or unwarranted Terry stops are at the core of that problem.

The stop and frisk remains a valuable police procedure, and when executed correctly to the letter of the law, serves the public at large, which was the presumed intent of the court in Terry. However, somewhere along the lines, the Terry stop may have become divisive and an excuse for police to act irrespective of the law, all the while being shielded by that same law. For that reason, it is understandable that American citizens were outraged by Donald Trump’s suggestion of a resurgence of stop and frisk. The interesting part about this proclamation, as stated earlier, is that stop and frisk technically isn’t unconstitutional under the strict guidelines of Terry, but rather it is the application of the stop and frisk, as in the case of Floyd, that leaves a bad taste in the mouths of so many Americans; black and white, Hispanic and otherwise. Thus, until the data analytics lead to the conclusion that the stop and frisk is being applied in a racially neutral manner, or at least have the appearance of racial neutrality, people will remain wary of this constitutionally sound police tactic.

Student Bio: Harrison is a 3L at Suffolk University Law School, and a Lead Blog Editor on the Journal of High Technology Law. Harrison is also the President of the Suffolk Law Intramural Basketball Association, and the Vice President of the Law Innovation Technology Student Association. Currently, Harrison is interning with Harvard Law School’s Access to Justice Lab, and working closely with the Massachusetts Trial Court system implementing guided interview and document automation software.

Photo credit to http://warondrugs.justicesos.org/

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog are the views of the author alone and do not represent the views of JHTL or Suffolk University Law School.