By: Hayden Gramolini

Modern technology has drastically changed day-to-day life over the last twenty years and sports are no exception. It would have been unfathomable to prior generations that running backs would be wearing speedometers to track their top speeds and algorithms would be used to determine the launch angle of a batter’s swing but both are commonplace nowadays. In addition to its impact on strategy, technology has revolutionized the way that sports are consumed which poses concerns for the traditional licensing structure of the television agreements that make sports so profitable.

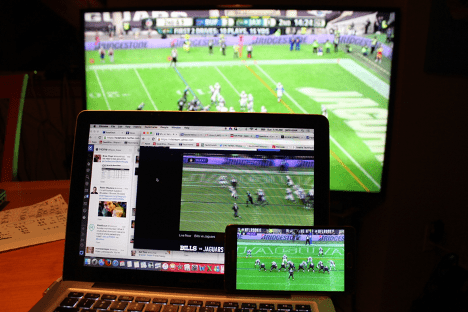

For the majority of its existence, sports fans were limited to viewing their local teams’ games and a few nationally televised games per week. Around the turn of the century, almost every professional sports league developed a premium satellite package to watch all televised games like NFL Sunday Ticket or NBA League Pass. These packages tend to be extremely expensive for the average consumer (For example, NFL Sunday Ticket is $293.94), and like everything else in the world, people found a way to cut corners to get their content. The business model is essentially as follows, someone who pays for one of these premium sports packages records the game live and broadcasts it on the internet while receiving money from advertisers and/or donations from subscribers. Illegal streaming has become more and more normalized in modern America. Instead of paying these high rates for premium access to sports, a large percentage of fans turn to the internet to solve their problems.

This phenomenon has large adverse effects, however. A massive portion of sports revenue comes from television contracts. For example, the NFL is currently in agreements with FOX, CBS, NBC, and ESPN for broadcast rights through 2022 which they collect a total of $4.5 billion per year. In return, these networks have the exclusive license to broadcast certain games pursuant to the terms of the agreements. A license is a contractual right given by a qualified authority to do something that would otherwise be unlawful. In this situation, the NFL is the qualified authority as they own the right to broadcast their own sport and CBS, for example, retains a license to broadcast specifically games at 1:00 p.m. and 4:05 p.m. on Sundays. This licensing agreement is a mutually beneficial bargained for exchange as the NFL receives a massive about of money to allow the network to show the game, while the network then gets paid by other agreements to advertise during the broadcast to offset their costs.

The main metric for these networks to gauge the value of their broadcast licenses is Nielsen ratings. The cord-cutting generation is largely reliant on streaming as a cost-free alternative but every person that streams a game illegally is not recorded as a Nielsen view for these networks. Therefore, when this is done in large quantities, there can be drastically different numbers in recorded viewers and actual viewers. When recorded viewership is down, the networks will value the broadcast licenses as less profitable and adjust the amount they are willing to pay proportionately. In turn, sports leagues will have less money to bring to the collective bargaining tables which could adversely affect things like athlete salaries.

Nielsen ratings indicate the opposite of this currently but there is good reason to believe change is in store. For instance, the Super Bowl brought in a recorded 99.9 million viewers this year which was up 1.7% from 2019 so it appears good on paper. The problem arises when you analyze where those numbers are coming from. The overwhelming majority of fans that watch games on illegal streams are under the age of thirty-five. The Nielsen ratings are therefore largely reflective of older populations and as generations go by, it seems as though streaming is not going anywhere so the percentage of traditionally viewed games will likely go down. Running parallel to the recent success of ratings has been the fact that sports have never been more popular than they are today. Athletes dominate pop culture in general as well as their respective sports. We have seen considerable growth in professional athletes’ visibility in areas like social justice, media, acting, and music. With all of these alternative outlets for athletes, the sports world has collectively succeeded. This general success is likely reflected in viewership as one would imagine, while this is obviously a good thing for the industry, it is not sustainable as the baby boomers still make up a large portion of viewership who will not be there forever.

This dilemma could have very dangerous consequences down the road. The sports world could see reduced cap structures as a result which would decrease player salaries across the board. This problem is emblematic of a larger issue in sports and that is the inability to measure popularity in the modern age. Difficulty in gathering data on illegal streaming is just one example of many. Social media has revolutionized the consumption of sports as well. Sports highlights regularly get millions of views on social media websites and this too is an incredibly complicated metric to put a dollar sign to as these are essentially free views. Executives at league offices have a very tough job to do moving forward in negotiating broadcasting agreements when the ability to demonstrate the value of the sport is becoming ever more intangible. In order to overcome the complications that mitigating factors like illegal streaming and social media impressions cause, business executives in the sports world will have to rethink the way they intake data to negotiate effectively.

Student Bio: Hayden Gramolini is a third-year law student at Suffolk University Law School and a staff member for the Journal of High Technology Law. He attended Quinnipiac University for his undergraduate degree where he majored in Legal Studies and minored in Sports Studies. He has a strong interest in practicing In-House in the future and recently declared for a business law concentration.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog are the views of the author alone and do not represent the views of JHTL or Suffolk University Law School.