By Nebyu Retta

A Complex Energy Market

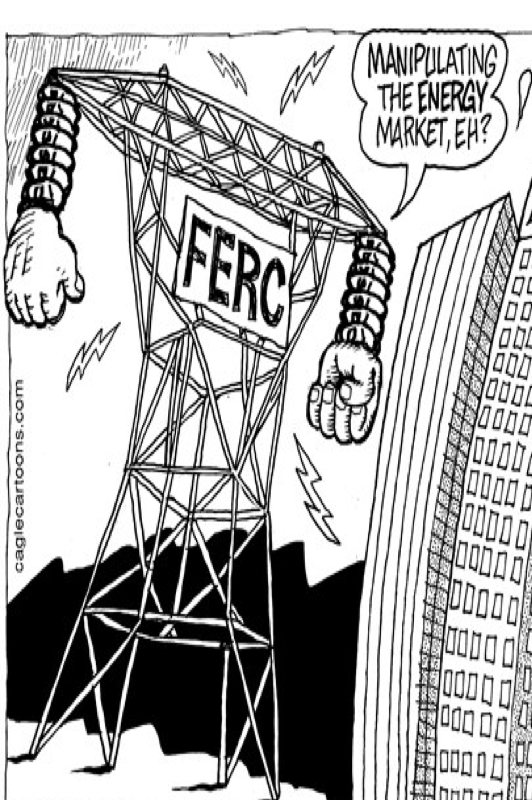

Once upon a time, the utility markets were vertically integrated. Generation—distribution and transmission were controlled under a single firm. With the emergence of regional transmission operators and independent systems operators—and the increased regulatory complexity of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (“FERC) — a not so bright jurisdictional line between Federal and State authority in the energy market remained. However, 2016 was a key jurisprudential moment for the Supreme Court.

A Unanimous Holding

Recently, the Supreme Court, in Hughes v. Talen Energy Marketing, issued an 8-0 decision ruling that the Federal Power Act (“FPA”) and FERC preempted a Maryland regulatory program promoting in-state generation through guaranteed capacity payment. 136 S. Ct. 1288 (U.S. 2016)

The jurisdictional divide between states and the Federal government in the wholesale capacity market has always been as such:

- Under the FPA, wholesale and interstate transactions are controlled by the Federal government, through FERC;

- While retail transactions, including control over in-state generation facilities, fall under the state’s umbrella.

Maryland wanted new natural gas generation within its borders. Why? —the wholesale capacity markets—operated according to FERC-approved rules—meant to incentivize new construction on a regional basis through a wholesale capacity auction. Maryland believed this did not provide sufficient price signals to encourage the new construction, which Maryland hoped for.

As a result, Maryland enacted a statute to subsidize a new natural gas plant by making up the difference between the capacity market clearing price and what the new natural gas plant needed to attract investors. This was found to be preempted by the FPA.

The Supreme Court rejected Maryland’s efforts to circumvent FERC’s authority by guaranteeing chosen generators a specific capacity price.

Renewable Industry Unscathed by Decision

The Hughes holding was tailored specifically to the facts of the case—not to the renewable energy community. Ongoing state efforts to spur clean energy technology have therefore not been obstructed by this decision—a clear victory for the renewable community.

So, what kind of Preemption, exactly?

What we know for sure is that Maryland’s scheme was preempted. But it is still uncertain to what degree.

Concurring directly from the bench—Sotomayor seems to be a bookend on one end saying only conflict preemption (which is one of the implied forms of preemption) and Thomas as the other concurring bookend saying it was express preemption. Thus, while the majority talks about both conflict and field implied preemption—the decision ultimately affirms the 4th Cir. which held both forms of implied preemption were present. So, the position between the two concurring bookends is at least field preemption, between express preemption (Thomas) and conflict preemption (Sotomayor).

It is important to look at how the parties presented and framed the issues in the matter to the Supreme Court. To keep this in context, the federal trial court determined that there was conflict preemption; the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals concurred on conflict preemption and also found held that there was field preemption. The matter on appeal held that both types of implied preemption were present.

From a standpoint of litigation, Maryland’s brief could have made the argument that one of these two types of preemption was obviously even less present. In which case—the Supreme Court not adopting such a distinction would mean that Maryland was essentially not convincing in getting one of these discarded. However, Maryland went for the double-entendre—arguing that neither form of implied preemption was present.

Thus, the Supreme Court’s holding essentially affirms that Maryland’s scheme was preempted by virtue of conflict and field preemption.

What’s Next?

The Court essentially dismissed the challengers’ program on extremely narrow grounds. However, states can still procure clean energy through long-term power purchase agreements. Nothing in this decision prohibits states like Illinois from investing billions in clean coal facilities—or off-shore wind in Massachusetts—so long as states don’t disregard FERC’s interstate wholesale market rate.

Although a careful analysis of the Court’s decision based on the parties’ briefs etches a clear bright-line—litigants will likely still litigate the preemption issue, until the Court provides clearer guidance.

Student Bio: Nebyu, Candidate for JD, December 2016. He is a fourth-year evening student and Lead Articles Editor of The Journal of High Technology Law. He also serves as a Litigation Assistant at the Energy and Environmental Bureau of the Mass. Attorney General’s Office.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog are the views of the author alone and do not represent the views of JHTL or Suffolk University Law School.