By: Jenna Connors

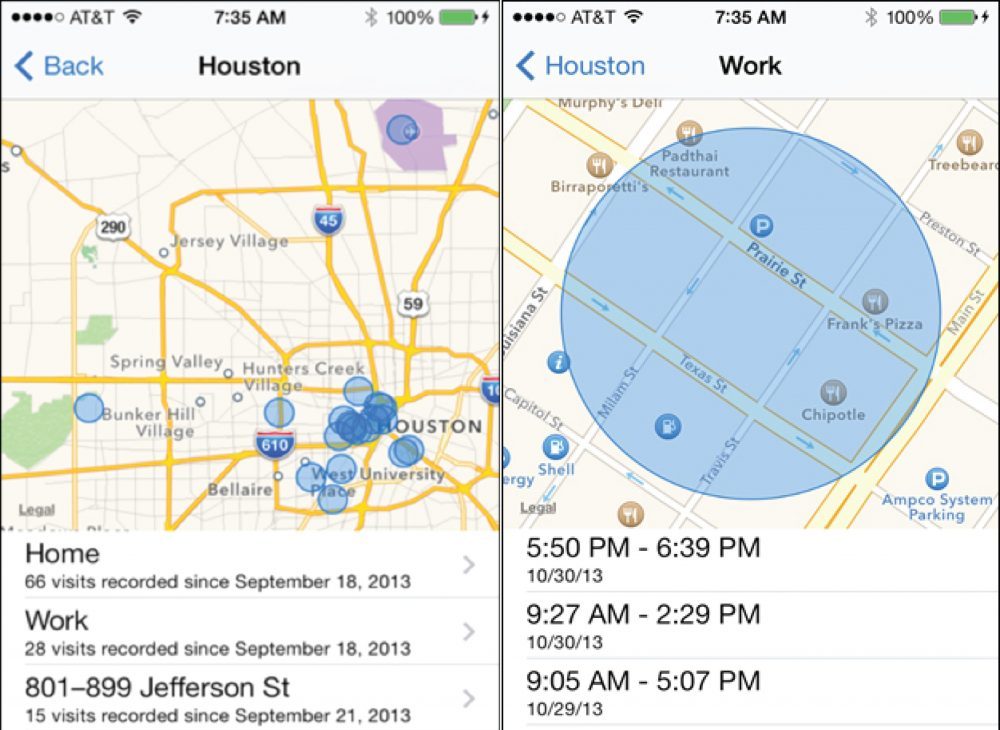

In 2011, police arrested four men, including the petitioner, Timothy Carpenter, in connection with nine armed robberies occurring over a two-year period at RadioShack and T-Mobile stores in the Detroit area. One of the conspirators admitted his guilt and provided the police with 16 different phone numbers from stolen phones called or received by around the time of the robberies. Under the Stored Communications Act, which only requires an order from a magistrate judge deciding that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the information sought is relevant and material to an ongoing criminal investigation, the government obtained orders a total of 127 days of historical cell-site information. This information included the location of the cell towers that handled Carpenter’s calls and texts indicating that he was within a certain distance of that tower when a call or text was made. The Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals held that the Fourth Amendment did not protect this information because obtaining records through a cell phone provider under the third-party doctrine does not constitute a search.

It is unclear whether the Supreme Court will find these orders constitutional since the police did not actually seize Carpenter’s phone to search through its contents. Additionally, the orders did not even pinpoint the exact location of Carpenter’s phone during the calls. The information only provided the government with how close the he was to the specific cell phone towers at a given time. Moreover, most of these cell phones did not even belong to Carpenter —they were numbers assigned to cell phones stolen from RadioShack or T-Mobile. In another Fourth Amendment case regarding warrantless GPS searches, United States v. Jones, Justice Sotomayor states “it may be necessary to reconsider the premise that an individual has no reasonable expectation of privacy in information voluntarily disclosed to third parties,” suggesting that future searches that may implicate the Fourth Amendment can be satisfied with this third-party doctrine because there is no reasonable expectation of privacy.

On the contrary, it may not have been difficult for the government to obtain a search warrant based on probable cause with more specific parameters since one of the men involved provided detailed information that linked the Carpenter to the robberies. This order spanned more than four months, and society may not be as willing to say that it is reasonable to obtain data about a person’s location for such an extended period of time. There is a vast amount of information available to the government through a cell phone provider that would implicate a person’s privacy rights, such as information about your home or other daily tasks for which Americans use their cell phones. Access to this information could be constitutional by simply applying for a warrant.

The most important takeaway from this pending decision is how the police could find ways to circumvent the Fourth Amendment by using the third-party doctrine to obtain information from cell phone providers. The government may not need to seize the cell phone itself if it can go through a cell phone provider, making the warrant requirement established by Riley v. California obsolete. However, simply because the government could have received a warrant does not mean that it was constitutionally required to do so. The Supreme Court could likely rule that the Fourth Amendment did not apply but will limit the third-party doctrine to instances in which the government is not looking for specific information, such as a person’s specific location coordinates.

Student Bio: Jenna Connors is currently a 2L at Suffolk University Law School and a staff member of The Journal of High Technology Law interested in criminal defense. She holds a B.A. in political science from Assumption College.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog are the views of the author alone and do not represent the views of JHTL or Suffolk University Law School.