By Thomas J. Mehlich, Staff Member

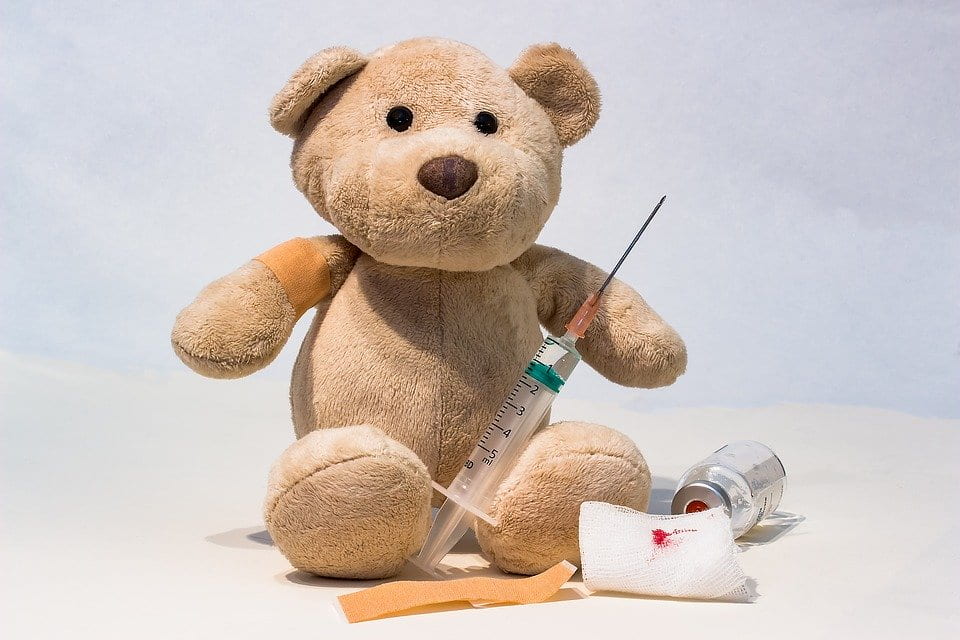

A week before I began my second year attending law school, it dawned upon me that I needed to get my flu shot. School was starting soon, flu season was right around the corner, and I was going to be surrounded by a vast number of students and faculty in a single university building… the perfect breeding ground for influenza to spread. It was a simple process: I hopped in my car, drove to the local CVS Pharmacy, walked up to the pharmacist’s counter, and told her that I would like to get my flu shot that day. After a couple signatures and a small pinch on my left shoulder, I was vaccinated, with the entire process taking no more than twenty minutes.

Unfortunately, getting an influenza vaccine is not as simple for many other Americans, particularly children. According to a recent news article, thirty states currently limit the minimum age upon which a child can receive a flu shot from a pharmacist instead of their pediatrician. Some states, such as West Virginia and New Jersey, require the child to obtain a prescription from a physician before authorizing a pharmacist to administer the child’s vaccination. The only way for children who fall under the restrictions to receive their vaccine is through a physician, which presents a number of barriers in and of itself.

Before discussion of children’s access to flu vaccines, it is essential to understand that the government considers influenza vaccination campaigns critical to public health. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the leading national public health institute, recommends that every person receive a flu vaccine each season starting at six months of age. The CDC takes the risk of influenza outbreak so seriously to the point that the organization publishes a “Weekly U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report,” regarding the current state of influenza-like illness (ILI) in America.

According to the CDC’s January 24 report, 37 jurisdictions have reported high ILI activity. The same report also acknowledged that there have already been 54 influenza-associated pediatric deaths during the 2019-2020 flu season, and approximately 8,200 flu-related deaths overall in the United States. Last year, there were a reported 136 influenza-associated pediatric deaths.

At the same time, the CDC estimated that during the 2017-2018 flu season 74% of children eligible for influenza vaccination were not actually vaccinated. While some of the common reasons for children not being vaccinated include parental concerns about alleged vaccine side effects and parental beliefs that their child is not at high-risk, a significant cause is lack of access. According to CNN, three states (Florida, Connecticut, and Vermont) do not allow children to be vaccinated in pharmacies at all – and another 30 states have pharmacy vaccine age restrictions for certain children.

Take Massachusetts for example, a state that has the second-highest number of physicians per capita in the United States. While Massachusetts has a high volume of physicians, there are 107 municipalities in the Commonwealth that do not have a single primary care physician. It is estimated that 41% of the state has little to no convenient access to primary care physicians, particularly in the rural areas located in the western part of the Commonwealth.

All of this begs the question: Do the states have any legitimate interest in regulating the age during which a child can receive a flu vaccine from a pharmacist? The brief answer is no. The American Academy of Pediatrics, a professional organization made up of 64,000 pediatricians, sees no issue in children receiving vaccines in a pharmacy setting, particularly because pharmacists are trained to administer vaccines. Potential liability issues that may arise if such restrictions are lifted are not of any legitimate concern, as states can pass statutes that grant pharmacists and their interns’ immunity from any injuries sustained as a result of vaccination.

Furthermore, the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986 limits liability for all vaccination administrators, not just physicians. Under the Act, an individual may be compensated for influenza vaccine-related injuries and deaths under the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program. Even if pharmacists had liability concerns, lifting these restrictions would not force them to start administering vaccinations; it would merely give them the ability to vaccinated all children. Some physicians have reservations about “continuation of care” when allowing their patients to be vaccinated at a pharmacy. Children under the age of nine may need a second influenza vaccination a month after their first depending on their past vaccination history, which would require a complete immunization record. Once again, that is not a legitimate reason to uphold age restrictions. Parents interested in vaccinating their children in a pharmacy could simply obtain their child’s records, assuming their physician is willing to cooperate. Physicians and pharmacies already have a unique relationship that requires a significant amount of communication.

States will never fully control influenza outbreaks as long as they restrict children’s access to the vaccines. It is proven that lifting restrictions leads to more vaccinated children. In January 2018, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo issued an executive order permitting pharmacists to administer influenza vaccinations to children age 2 and older. Previously, New York children could not be vaccinated at pharmacies at all. Four months after the executive order issued, about 9,000 children received flu vaccinations from pharmacies. Other states must follow suit to minimize the potential number of flu-related deaths. Expanding access could provide a great benefit to the state of public health among children in the United States.

Sources

https://www.cnn.com/2019/11/26/health/flu-shots-children-pharmacy/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm

https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1718estimates-children.htm

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/laws/state-reqs.html

https://commonwealthmagazine.org/health-care/ma-primary-care-doctor-desert/

http://www.statemaster.com/graph/hea_tot_non_phy_percap-total-nonfederal-physicians-per-capta

42 U.S.C. § 300aa-10 (establishing the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986)

42 U.S.C. § 300aa-11(a) (minimizing liability for vaccine administrators)

42 U.S.C. § 300aa-14(e) (inclusion of seasonal flu vaccine in Vaccine Injury Table under the Act)

Thomas J. Mehlich is a second-year student at Suffolk University Law School. He is currently working as a law clerk at boutique law firm based in Braintree, MA that specializes in representing commercial and residential property owners and managers.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog are the views of the author alone and do not represent the views of JHBL or Suffolk University Law School.